Caithness Art and Stone Festival

4th – 16th August 2025

Halkirk

The Caithness Art and Stone Festival was a two-week long pop-up exhibition funded by the Halkirk ABH Fund and Watten Windfarm, administered by Foundation Scotland. The annual exhibition is a celebration of local artists work, provide networking opportunities to support working in art, and bring people to the Ross Institute in Halkirk.

Thick cotton material stretched over temporary frames are the basis of the space, with white plinths throughout and bright exhibition lighting illuminating a really beautiful collection of photography, visual art and sculpture by artists living and working in Caithness.

The theme of this exhibition was Caithness rocks and minerals; from quarries to outer space. Artists were asked either to produce new work for the exhibition, or to display work already in existence.

New works included Oakley Cundalls’ series of six black and white film photographs which were placed along the back wall of the gallery. Crumbling walls, churchyards and empty crofts signal a passing of human time. These structures were erected by people a few generations before us, and forgotten by the generation after. Oakley’s careful photography restores a sense of care to them, and doesn’t lament the gentle decay. Nature in Parallel, a portrait photo taken on a Kentmore 400, compares a much greater passage of time: a figure on a manmade pier of the right is contrasted with nature’s continuum between land and sea. Two outcrops of rock which were formed over millions of years, which saw changes in sea level, climate and species sit on the left. This exhibition reminds us that rocks do form: they weren’t always there, and the stone formations which look so permanent to the figure on the pier grew from somewhere and will shrink away again one day.

In front of Oakley’s series are a selection of sculptures by ceramicist David Kinghorn. In clay, oxide and resin, David builds up Sea Stacks I & II, Wild Geos, Igneous Intrusions and more. These are earthy, cumulative pieces which speak of layers, geological and biological forms and the dark, sticky substance of life which bind it all together. Visitors found them evocative of Totem poles, the Middle-Earth, the Discworld and the heavenly circle and physical squares, Tiān Yuán Dì Fāng, of Chinese architecture. Time and space become vectors only of the imagination of the viewer here – they can project onto the sculptures the pasts, presents and futures they wish to. Whatever they inspired, or were inspired by, they were a great draw in the gallery space and we look forward to visiting David in September as part of the Dunnet and Brough Open Studios on the 20th and 21st.

Further forward, keeping to the centre of this cavernous and cavey space, are Iain Macleans carved bowls. There are two bowls: the Stone Basin which is a vision in glossy black and the much more enclosed Quartz Stone Bowl which glitters with veins of colour through it. Each piece is a basin shape carved into the natural rock shape, Stone Basin into what looks like a huge gleaming back pebbles and Quartz Stone Bowl into a chunk of rock which could sit in a large hand. The two polar opposite pieces are tied together with Celtic Cross hewn with a selection of screwdrivers, and Stone Ball which is a contemporary study of a found artefact. The maker describes the nature of the pieces such as who inspired them, who they were gifted to and what he thinks the Stone Ball is. The cross was a gift for a relative‘s discovery of faith, and the ball’s purpose is more open to interpretation. Iain humanises the long history of working with stone, from the tolls to standing stones, through gargoyles and into the present and 21st C brochs. Read more here.

The sculptures in the space give dynamism and maybe even an organic but mathematical stalegmite feel. The faux walls along either side show flatter works; school pupils pictures of Bismuth, Stonehenge, Amethyst, Meteorites and more are along the left beneath portraits of local people nominated as ‘Rocks of Support’, and along the right are the slowly multiplying Duncansby stacks in watercolour, a digital collage exploring Uranium by Caroline Swan, stone texture in ink by Jess Sutherland and a fantastically stylised Dippy the Dipterus by Rising Artist Anne Ruddy.

A Noble Journey is a piece no larger than 7cm high. It is made of vanilla coloured resin, and inspired by the legendary Skinnet Stone nearby in Morissons park in Halkirk. The original stone dates back to around the 10th century AD, soon after Christianity appeared in Caithness with Saints Fergus and Drostan in the 8th century. The Pictish carved stone does show symbols of Christianity, but what was inspiring to the artist was the carvings of hippocampi, or waterhorses, the elaborate knotwork and what appears to be a chariot carrying Pictish Nobility at the bottom of the carvings. After seeing the unveiling of the replica Skinnet in Halkirk in May 2025, Voxaetern’art got to work digitally sculpting this piece of work.

Using Zbrush, Vox replicated the complex patterns of the original carvings and expanded them include his signature candle-figure. The chariot becomes an ammonite ridden through the North Sea waves by the ultimate noble-person, the character “Eisth”, and harnessed to a fantastical water-horse. The scene erupts from the stone as an excessive relief, with Duncansby stacks behind them, and tiny salmon splashing through the waves. It is theorized that these Pictish stones were once painted.

Using Zbrush, Vox replicated the complex patterns of the original carvings and expanded them include his signature candle-figure. The chariot becomes an ammonite ridden through the North Sea waves by the ultimate noble-person, the character “Eisth”, and harnessed to a fantastical water-horse. The scene erupts from the stone as an excessive relief, with Duncansby stacks behind them, and tiny salmon splashing through the waves. It is theorized that these Pictish stones were once painted.

Vox Aetern’art creates and prints scenes as a contribution to the world of miniature painting. Where so often, miniatures depict warriors, war, and formation, Vox’s work counters this with free-flowing imagination, adventure and the hall-marks of Greek classical sculpture in bite-size. Here, the viewer is taken into the future: their own painting brings to life this historical scene, technology becomes a tool for adventure rather than subjugation and the new can be embraced, albeit with wisdom.

Other pieces in the exhibition explored transformation: Kirsty McKinnon’s Creogh na Mara features sea glass – fragments of bottles, boat running lights, Depression era tableware and other items which have dropped in the ocean in one place, and turned up smooth and mystical on the shores of Caithness. Dylan Cundall uses Caithness minerals to create glazes. By gathering and burning what he finds in the landscape: peat, salt, feldspars and copper might all be found here; glazes for ceramics and jewelry are created. Heat here is used as a catalyst for transformation, and the same is seen in Susan Marshall’s wild clay stones. Amongst the incredibly tactile worry stones, runes and selkie bowls are a clay and wild-clay combinations which show how materials react to the temperatures they are exposed to. Susan’s work seems delicate, but the depth of the significance of Norse, Celtic and local culture to her work gives it a gravitational pull.

Justine Bainbridge’s work uses heat in its formation of layered glass, space in its’ incorporation of materials such as gold panned in Caithness, felting, fossils, moss, ceramics, and duration.

In the collection of Justine’s work is a small bowl holding an ochre-colored sedimentary rock, white pebbles, a grey stone and a piece of fossil covered in vivianite. Vivianite is a mineral which forms on organic materials in watery environments, such as bogs and lakes. With exposure to light and oxygen following long submersions in rock or water, vivianite oxidizes and becomes a vivid blue ochre.

This and other sources of pigment have been collected by Justine from the landscape and ground down to extract a stunning array of colours. These are shown in tiny glass jars, with Dunnet forest charcoal. To bring these bottles of colour, Justine traipsed through the landscape on constant alert for rocks and pebbles of a specific type and hue. Instead of letting her mind wander and celebrating or condemning what weather there was, this artist took each step with the idea that it would bring her closer to the goal of creation.

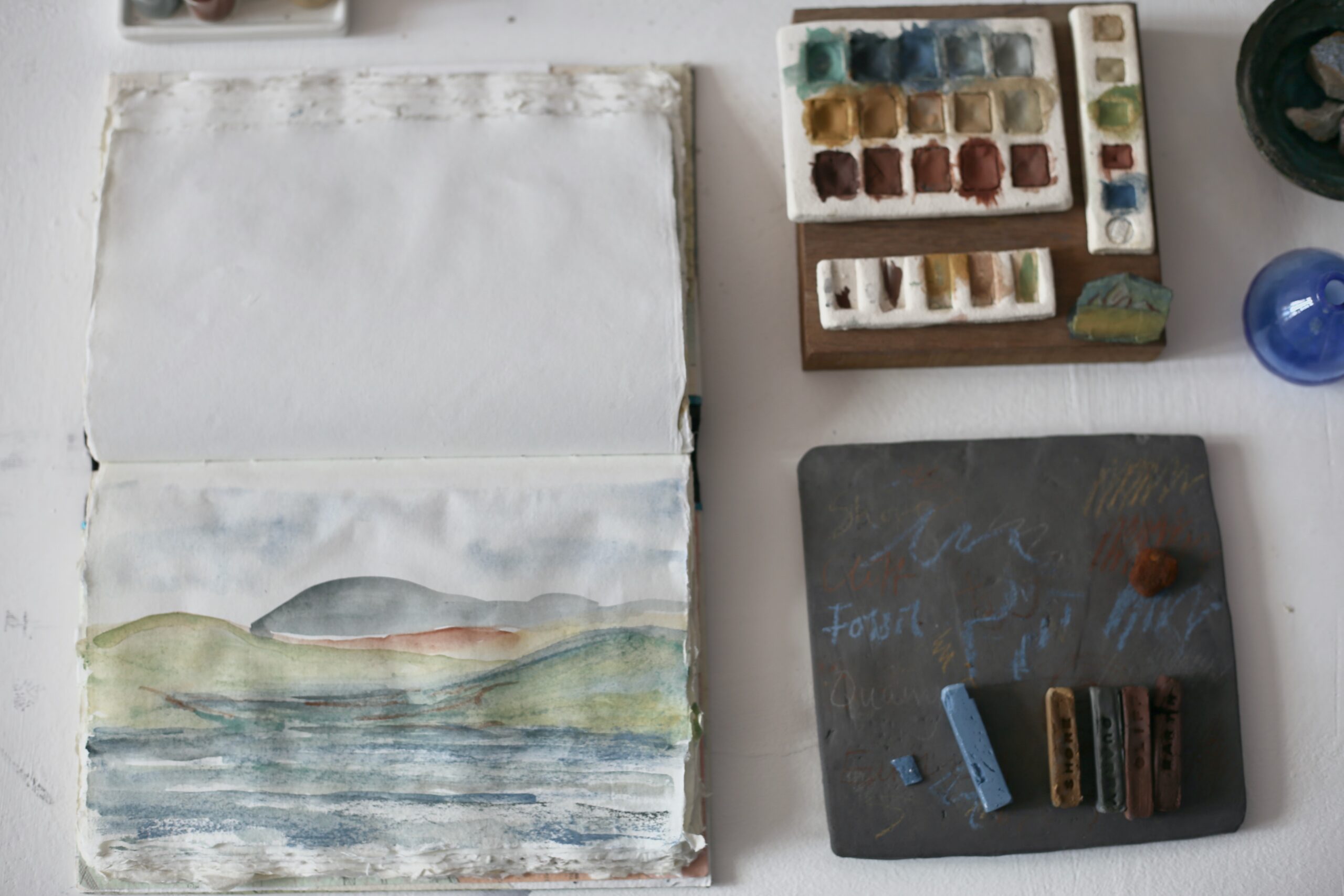

Once collected, these categorized rocks and pebbles were ground down do produce rock residue and the colored powder of pigment. There may have been more to this geological sorcery but this writer has yet to find that out. This powder was then turned into the bottles, a set of chalks, and 2 sets of watercolour paint which, with the open sketchbook next to them, compelled the audience to try out these hand crafted paints.

The gallery visitors did. Justine’s work produces such transfixing alchemy that even the least artistically-inclined tried their hand at mark-making in the book. The outcome will be a record of impulses, charm and magic that Justine can look back over to know what her work inspired. By inspiring action, the artwork is radical, transformative and powerful. This is bewitching work by a artists who’s secret ingredients included the time she spent observing, collecting, grinding, mixing and making.

A historical mark – “I woz ere” which was sprayed across Caithness, and doubtless further, was an unholy declaration of selfhood a generation or so ago. It would have been made in oil-based spray paint at best, and then repeated across the county, and then in biro on notebooks at school. It was next echoed in Lindsay Gallacher’s They Made it Their Own, a tribute to anti-art in resin which showed a defaced drystone wall. Graffiti has popped up locally with stunning, murals in Thurso and Wick – is it the time to refine our techniques and make more? Environmentally concerned (if not environmentally-friendly) spray paints are now available and there is a good livelihood in council-sanctioned street art. This piece had previously only been shown in public once before, so it was a rare opportunity to see it.

A final transformation came with Anne Grain’s merino wool pebbles. In exquisite detail she replicated old red sandstone, ammonite fossils, the Devonian fish, granite, jasper, quartz and chert. So realistic were these that after seeing the exhibition, visitors more than once assumed that the items would be heavy – it was with delight that they were found not only to be light, but soft!

Around the seating area, where visitors could sit, chat and ponder the real serious questions in life (what is art? Is it just a pile of rocks rearranged into something else at a different time? Is that the beauty of it?) are fabric rocks made by lots of different people. Some are crocheted in bright colours, some knitted in grey. Some are little rocks in knitted coats, and some are raw wool felted into hard little nuggets. Anne’s felted pebbles are joyful, well-studied, and well-made. A conversation with her and her husband Mike at the 2024 exhibition were part of the inspiration for this Art and Stone Festival, as much as were the Caithness flag stone industry, painted pebbles, the Stone Age, Brochs, the Sutherland space port and the origins of the alter stone at Stonehenge.

Tamara Hicks brought stone to the people in her Rock Stars piece. Two counter tops in Caithness Flag were cut into 80cm diameter circles at Norse Stone, a local quarry, and polished ready for making into the tops of stone bench at Halkirk Primary School. Before they are put in place, Tamara ran a series of 6 workshops where people could try out stone carving, and add to the countertops. From children, through creative’s, stone enthusiasts, jewelers, crafters and yogis, the contributors to the countertops grew a deep respect for the stone, and those who work with it.

Caithness flag is made up of millions of years of mud, silt, dead fish and volcanic ash which were pressed together to form this fine-grained and extremely hard substance. After trying out the carving of stars on softer stone like limestone, attendants to the workshop began on the vast and beautiful counter tops. The flag seemed to have a will of its own, but responded to patience and persistence.

Under Tamara’s expert guidance, a selection of stars in various sizes began to emerge on the heavy surface. The natural shades of the stone and its enormous weight imitate the night sky, the magnitude of space, and the gilt stars twinkle in real gold. This will be a gift to the community which will last many years, if not forever. A sensational legacy of the Caithness Art and Stone Festival.